Michael the Man

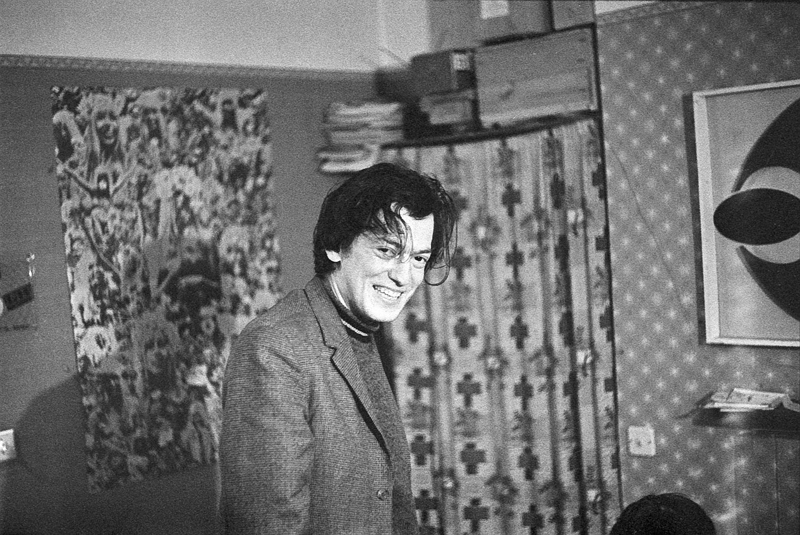

Michael in his room at 52 Walton Crescent (February 1969).

Michael was such an unusual person that many people found him off-putting at first. He was pale, thin, often with long unkempt hair and a dishevelled appearance. He fixed people with his intense gaze and talked non-stop in a voice with penetrating sibilants, which could easily be heard at a distance in a room noisy with conversation. He once admitted that he had made a phone call lasting for five hours!

Poor health

Michael suffered from ulcerative colitis and this seemed more troublesome than his asthma at the time. He would suddenly stop talking, murmur ‘Oh, God’, and disappear from the room. We had a rather cruel phrase for when he was in a bad way – ‘Michael is rather “Oh, God-ish” today!’ I took my own good health completely for granted, and had no experience in understanding someone with such severe, chronic illnesses. Now I feel guilty that I was less sympathetic than I should have been.

Poor health made it uncertain whether he would turn up for planned activities, and if he did, his behaviour could be unpredictable. On a good day there was plenty of laughter, and OUTRS members, particularly the less experienced ones, could learn a lot from him. On a bad day, when he was unwell and things were going badly, he could be disagreeable and find fault with everyone. He was a perfectionist and the rest of us didn’t meet his high standards. Some days, we wondered why we put up with it, and the less committed people were probably put off. But the core members kept coming back for more, realising that we had to accept Michael just as he was. We felt that what we were doing was really worthwhile, and Michael’s foibles were a price we had to pay. At the time, I didn’t realise just what a heavy price Michael also had to pay.

Acute hearing

Michael was blessed (or cursed!) with remarkably acute hearing. He claimed to be able to hear high frequency sounds well beyond 20 kHz, above the limit experienced by average younger listeners. He was particularly upset by the lower sidebands of the 38 kHz FM subcarrier, implying he could hear up to at least 23 kHz. Coupled with his analytical abilities, he was able to make judgements on the quality of performances of live and reproduced music that the rest of us sometimes struggled to follow.

He was keen to protect his hearing from excessively loud sounds, particularly of amplified music. I remember a modern music performance with heavy amplification at which he sat with his fingers in his ears. Afterwards I asked him why he didn’t just get up and leave. He replied that he couldn’t do this without risking his hearing by taking one finger out of his ear to pick up his bag!

At recording sessions

When Michael did turn up to a session, he was usually accompanied by one of his Revox tape recorders which he wheeled around strapped to a luggage trolley. He often carried essential items such as tape and connecting leads in bright red, white and black BASF plastic bags, so he was a distinctive sight as he made his way through crowded shopping streets to a Saturday afternoon rehearsal. When setting up, everything was done according to a ritual, and he would mutter to himself, ‘I am plugging the left hand channel into the tape recorder…’ In the days when stereo was only just gaining a foothold, connecting leads were often not colour coded, and he carefully painted a red or white band on the plugs to avoid any risk of channel reversal. He used some of his own accessories such as mains adaptors at OUTRS sessions, and he made sure these did not disappear into the general pool of equipment by labelling everything with a typed ‘MAG’ label. We thought this rather amusing, and was one reason why we referred to him as MAG! He was also meticulous in labelling tapes and their boxes, and carefully included programme notes in the box. We felt this was rather obsessive, yet it was obviously essential, and years later must have been extremely helpful to the people at the British Library Sound Archive (http://cadensa.bl.uk/cgi-bin/webcat) who have the marathon task of cataloguing his huge tape collection. Reading the catalogue entries, I can almost hear him murmuring to himself as he writes out the performance details.

Michael was perfectly happy when all was going to plan, but became distressed if there was a technical hitch such as hum, crackle or a loose connection. Then it was often Peter who would not only try to calm him down, but also analyse exactly where the fault lay and work out how to cure it. The tension became almost unbearable as we tried to locate faults and repair equipment as the starting time loomed! If all went well, everyone relaxed at the end of the performance, and there was a buzz of excited conversation as we all gave our opinions on what had happened.

Excellent company

When he was on good form, Michael was excellent company. He could often be found at tea time in the Mathematical Institute Common Room, holding court with anyone who would listen, on any topic under the sun, always with something insightful, controversial or irreverent to say. As a scientist, I found it was like a breath of fresh air to hear Michael expounding on music, the arts or current affairs, always with his grin of amusement on his face. In spite of his extraordinary abilities, he was never arrogant or patronising. This was a refreshing change from the behaviour of many students and academics who imagined themselves to be very clever.

Ill at ease

Michael was sometimes ill-at-ease with strangers, and particularly with women (who were a rare species at Oxford in those days, especially in technical subjects like mathematics and audio). When we went to collect the Dolbys from Dolbylabs, Michael approached the receptionist and tried to say something like ‘We’ve called to collect some Dolbys from Dr Dolby’, but evidently was embarrassed at using the inventor’s name to describe the product, and became completely tongue-tied, to the bemusement of the woman behind the desk. It seemed completely out of character in someone so talkative. Peter had to step in and explain why we were there.

Relationships

Michael appeared very sociable, to the extent that acquaintances found it was sometimes difficult to interrupt the flow of talk and get away without appearing rude. However, after I had known him for some time, I realised that he preferred to keep his distance. He seemed to be embarrassed by small tokens of friendship such as gifts or a birthday card, and he particularly hated the ritual of cards and presents at Christmas. Once, he said that we should work together for the good of OUTRS, not because we were friends who happened to share a common interest. In other words, we were not friends, but just people who worked together for the organisation. I found this hurtful.

At home

Michael lived on his own in a bed-sit (a single room) on an upper floor of 52 Walton Crescent, sharing the facilities with other occupants. The terraced house was convenient for the Maths Institute, in an area known as Jericho, which in the days before gentrification was considered rather seedy, and to be avoided at night. When I first knew him, we would sometimes be invited to his room to hear OUTRS tapes and music from his large and wide-ranging record collection, comprising everything from Bach to the Beatles via Boulez and Bartok. It included old 78 rpm records which he had found by scouring second-hand shops. It was a revelation to hear some of the classic performances by musicians such as Beecham played on good quality equipment. I still have a tape I made when I borrowed some of his 78s of great jazz musicians such as Benny Goodman and Coleman Hawkins. However, nobody was allowed to borrow or even touch his LPs. His studies on vinyl record wear made him acutely conscious of how easily the record could be damaged by mishandling, and by the stylus tracking (or more commonly, mis-tracking!) the groove, however good the equipment. Playing an LP involved a time-consuming ritual of cleaning the record and stylus, and woe betide anyone who even looked as though they might upset the process.

As time went on, his collection of records, books and tapes of our recording sessions piled up, and his room, always untidy, by his own admission became rather squalid. We were invited in less and less often, and finally not at all. In an era before mobile phones, the only way of contacting him was to turn up and ring the bell (which might not be working, or he might not hear it because he was listening to music). Eventually we threw stones at his window, which was flung open, Michael’s head appeared, and he glared at us unsmilingly and exclaimed ‘Yessss?’

Employment and Money

Michael’s financial position always seemed precarious, due to his difficulty in finding a ‘proper’ job. He was astonishingly productive at generating original ideas, but somehow found himself unable or unwilling to develop them to the point where they could be published. He also reacted extremely badly to deadlines, often becoming ill when faced with an examination or the need to submit work by a particular date. He never completed his doctoral thesis, which is the passport to an academic career, but once complained to me that he had enough material for three theses. However, he could not apply himself to the tedious business of writing up all his findings. At the time, I was struggling to produce enough results for my own thesis, and replied sharply, ‘Michael, just write up one of them!’

He would sometimes disappear for a few days at a time, and then reappear triumphantly with a completely new set of ideas on a completely new topic, usually unrelated to whatever he was enthusing about the previous time we saw him.

In spite of the lack of regular employment, he always seemed to have enough money for books, records, blank tape for recording sessions and especially equipment. Most of his personal playback equipment and tape recorders were purchased second-hand, not just because they were cheaper, but because he considered them better than their later equivalents. He invested heavily in the Calrec microphones which were purchased new, and were essential not only for the tetrahedral recording experiment, but also in figure-of-eight output for many subsequent recordings. It was extraordinarily generous of Michael to lend this delicate and expensive equipment to OUTRS, considering the high risk of loss or damage in the usual chaos of recording sessions, even ones in which he had no personal interest. Furthermore, he also purchased a pair of new Spendor loudspeakers for the tetrahedral experiment, and these were sometimes found in other OUTRS members’ rooms, ostensibly for surround sound tests.

At various times, he considered the possibility of full-time employment at Dolbylabs ‘(see The Dolby Experience), the BBC and Bell Labs in the USA. We soon learned not to keep asking him about these leads, because nothing ever came of them.

Humour

Michael had an irreverent sense of humour, greatly enjoyed ‘The Goon Show’, and liked puns and playing on words. For example, he published a spoof article proposing a system for encoding and decoding four channels so that they may be stored and transmitted via conventional two channel media. He called this ‘The J.O.K.E. System’, in which the abbreviation stood for the highly contrived name ‘Jointly Operated Kompression-Expansion’! (Hi-Fi News pp 843, 847, June 1970).

He used the pseudonym ‘Mike Anthony’ for light-hearted articles, Anthony being his second given name. He was well aware that insiders would know he was the author, and there was an added irony because nobody who knew him ever called him ‘Mike’, either to his face or otherwise. He was also conscious of the shortened version of his name being the abbreviation for ‘microphone’. Mike Anthony published an article on audio jargon, including the following examples (Studio Sound p 72, July 1974):

Ambience. A sort of muddiness added to sounds to make them less clear.

Coincident microphones. An arrangement of directional microphones which are spaced apart by more than five wavelengths of the highest audio frequency.

Stereo. An obsolescent term meaning a hi-fi system in which two speakers are missing.

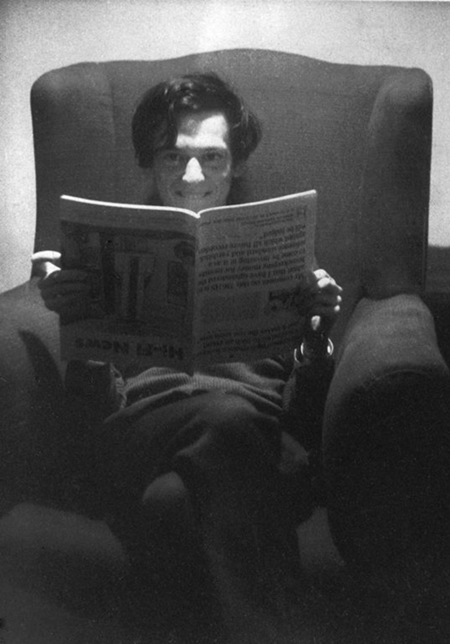

He had a strong sense of the visually absurd, as can be seen from some of the photos, for example, drinking tape head cleaning fluid, licking the Soundfield microphone and reading Hi-Fi News upside down

Epilogue

During the period covered by this article, Michael was regarded by many people as a crank, and by some in the audio industry as a dangerous crank. I find it particularly gratifying that his work eventually secured recognition in his lifetime from the Audio Engineering Society, in the form of a Fellowship in 1978, and a Gold Medal in 1991. The Gold Medal is the highest award made by the AES, and is given in recognition of outstanding achievements, sustained over a period of years, in the field of Audio Engineering. A photograph of Michael in the Society’s journal is accompanied by a caption stating ‘Michael A Gerzon graciously accepts the Society’s Gold Medal, its highest honor, for his unremitting exploration of the theory and practical realization of surround-sound reproduction systems.’

For comparison, it is noteworthy that Ray Dolby did not receive a Gold Medal until the following year, in 1992! (see The Dolby Experience )

Furthermore, the AES honoured Michael with a Publications Award in 1999, three years after his death, for the outstanding paper published in the Journal of the Audio Engineering Society during the previous two years. This was for a paper he co-authored with Peter Craven, entitled ‘A High-Rate Buried-Data Channel for Audio CD’, (Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, vol 43, No 1/2, 3 – 22, 1995 January/February). Peter recalls, ‘I received the award on May 8th, 1999, from conductor Lorin Maazel, who had been invited to the ceremony. A bit embarrassing as the paper was almost entirely Michael's work!’

‘Michael – silly’ is Paul Hodges’ apt title for his picture of Michael reading Hi-Fi News upside down. (Photo copyright Paul Hodges)